- Lot

- Information

Over the centuries, tea has played an important part in Chinese people’s lives. The origin of tea was dated back to the first emperor of the Ming dynasty, Hongwu Emperor, also known as Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-1398). On the sixteenth day of the ninth lunar month of the twenty-fourth year of the Hongwu reign, Hongwu Emperor has commanded to abolish the production of caked tea. Caked tea was popularized since the Song dynasty and was used widely as imperial tribute. However, it was extremely labour-intensive and took tremendous amount of effort and time to produce, particularly the production of carved figures of dragon and phoenix tea cakes. Thus, coming from a peasant background and experience as a civil administrator, Hongwu Emperor was genuinely concerned with the welfare of the farmers—he encouraged them to specialize in planting and harvesting loose-leaf tea. Since the Ming dynasty, selecting the finest tea buds, boiling them in high quality water in a teaware became the new practice for preparing tea. This has completely revolutionized and transformed the tea drinking habits of the people. This method is known today as the “boiling and steeping method”, also known as the “brewing method”. With the popularization of drinking loose-leaf tea, there are two major practices to enjoy a cup of tea—brew tea in a tea pot or pour boiling water over the tea leaf in the cup and let it steep. The latter method became the style of sipping tea in the Ming and Qing dynasties. As a result, the variety of tea vessels that were once used in the Tang and Song dynasties, including the pucker, the grinder and the large tea cooking vessel were gradually abandoned due to the simplified tea drinking habits. Nowadays, the main apparatus becomes the teapot and the tea cup.

Fig 1. Chen Hongshou's Tea Tasting

The present lot, a teadust glazed teapot, illustrates Yongzheng emperor’s discerning taste and pursuit of antiquities. It is characterized by a round globular body with a cylindrical arched side spout and an arched handle; the cover contains a round finial, the flat base is incised with Yongzheng four-character seal mark and of the period. The body of the teapot is covered with an even layer of tea-dust glaze inside out, with slight pinholes all over the glaze surface. The tip of the sprout, the outer edge of both the lid and the teapot where the glaze is thinner, are surrounded by a loop of brownish-yellow glaze. The tea-dust glaze reveals more of a greenish colour, resembling a cup of green tea with tea leaves afloat.

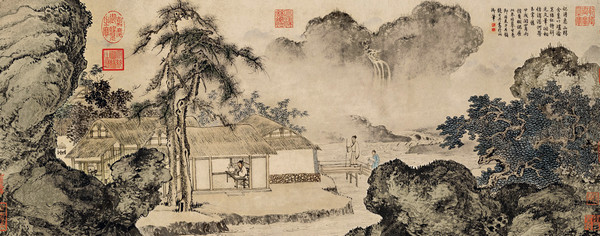

Fig 2. Tang Yin's Tea Tasting in Summer

Fig 3. Qiu Ying's Appreciating Pictures and Tasting Tea

The teadust glaze is one of the most important varieties among the iron crystal glazes of Chinese history. It is considered a high temperature yellow glaze; when glaze of this type is under fired in reduced flame, fine crystals will develop. The crystals look like the powder form of tea; hence the term "teadust" was coined. A famous Qing dynasty writer Ji Yuansou once praised in his literature on ceramics Tao Ya: “Teadust—a mixture of yellow and green colour; delicate yet unconventional; even more striking than flowers; as beautiful as the jade; the colour is very pleasing to the eye.”

In Tang Ying’s "Commemorative Stele on Ceramic Production" Taocheng jishi bei ji, the document listed teadust glazes were often simply designated "workshop glaze", depending on the specific colour, the glaze includes "eel-skin yellow", "snakeskin green" and "speckled yellow". Most of these different effects come down to firing temperature and processing of the raw materials. The teadust effect on the glaze surface was not artificially splashed on by the craftsmen; instead, it is caused by the crystallization of iron and lime silicates in the glaze when it undergoes firing process. The beauty of the glaze derives from its velvety-rich and glossy finish and the composition of greenish, yellowish and brownish micro-crystalline. Teadust glazes were often used to imitate the patina of archaic bronze, sometimes with overglaze enamel colours applied to the surface to suggest verdigris, or even gold to suggest inlay.

Fig 4. Teadust glazed teapot housed at the Palace Museum in Beijing

Fig 5 Teadust glazed teapot housed at Taipei Palace Museum

At present, two similar examples of teadust glazed teapots are found in the Qing Court Collection at the Palace Museum, Beijing (Fig 4), illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Colour Glaze, 1999, p.121; and at the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Fig 5), published by National Palace Museum, Empty Vessels, Replenished Minds: The Culture, Practice and Art of Tea, 2002, pl. 100. The current lot and two existing examples are all short and flat in shape. The pot finial is located at the midpoint of the teapot cover and the design is very well-balanced, with a taste of pure elegance. Compared to its two prototypes, this present lot has more of an even glaze surface. As shown on the image, the side sprout of the piece located in the Qing Court Collection was slightly over fired, as it contained more of a dark brownish colour. The other prototype’s sprout also was over fired and parts of its handle were unglazed. Without a doubt, the Yongzheng Emperor took great interest in the porcelains made for his court and commissioned items made under very strict supervision. Therefore, it is extremely rare to find a perfectly fired teadust-glazed product of such exceptional quality.