- Lot

- Information

Zao Wou-Ki

01.03.99

Painted in 1999

Oil on canvas

162 × 130 cm

The Chinese master abstractionist Zao Wou-Ki and his artistic expression are considered by many art critics and writers a “miracle,” or even a “l(fā)egend.” As the litterateur, Cheng Baoyi said, “Owing to the art of Zao Wou-Ki, the long wait for Chinese painting to escape its inherent confines has ended. The real symbiosis between the East and the West has finally appeared for the first time.” And the media both home and abroad has honoured him “the treasure of Chinese and Western art.” He was also the first to receive international recognition after the war among Asian artists who painted in the Western tradition.

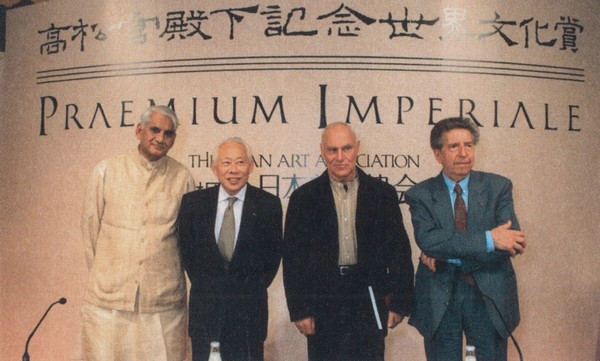

Zao Wou-Ki (second left) won the Japanese Royal World Culture Award (painting category) in 1996.

Born in Beijing, Zao entered the Hangzhou Fine Arts School in 1935. In 1948, he went to France to derive nourishment and inspiration from Western art. Placed within Western-style paintings and canvases, he pursued the artistic expression peculiar to himself during a 78-year career of painting. The “Hangzhou period” (1935–1950) laid the foundation of Zao’s artistic practice; the “Klee period” (1951–1954) enabled him to move forward towards abstraction; in the “oracle period” (1954–1957), Zao integrated the earliest form of Chinese characters into his paintings; in the “wild cursive period” (1958–1970), the bold and free composition was established; in the “Infinity period” (after the 1980s), he wielded the brush freely. Zao Wou-Ki learned from Chinese and Western cultural traditions and refined the essence of artistic creation. Through distinctive understanding and recreation, Zao constantly interpreted new forms of visual language, exceeding himself again and again, until perfection was attained.

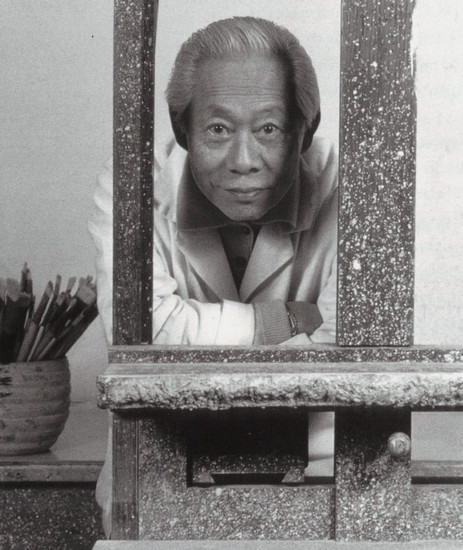

Zao Wou-Ki in Paris Studio in 1996

After the 1990s, Zao Wou-Ki was frequently invited to hold exhibitions at home and abroad, yielding brilliance in the art world. In 1993, he was awarded the “National Order of the Legion of Honour” by the former French President Fran?ois Mitterrand. In 1994, Akihito, the emperor of Japan granted him the “Praemium Imperiale” in the painting section. From 1991 to 1999, he successively held large retrospectives in important museums in Paris, Luxembourg, Spain, Japan, Hong Kong, Kaohsiung and Shanghai. In 1998, the retrospective “Zao Wou-Ki: 60 Years of Painting” was co-organised by the French Minister of Foreign Affairs and in Shanghai Museum, which then travelled to the National Art Museum of China in Beijing and the Guangzhou Art Museum, marking his acceptance by the Chinese audience. The presented work, 01.03.99, was completed at the peak of Zao’s international reputation.

Ju Ran

Landscape

156.2×77.2 cm

An Imposing Mountain and a Vision in the Heavens

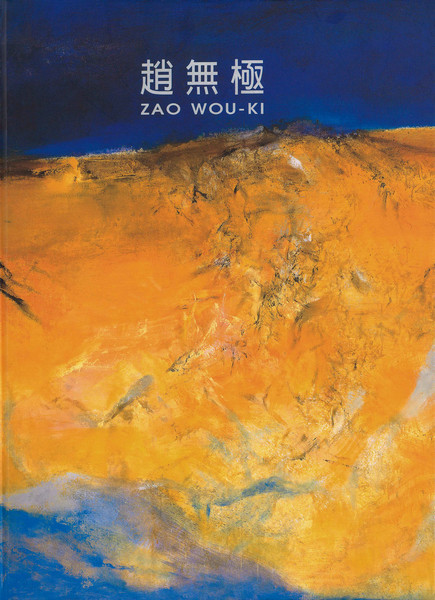

“The image is imbued with a lively rhythm, a non-figurative painting in yellow and blue hues, presenting the painter’s unrestrained and sincere characteristics. Inscribed on the back of the painting were the name and 01.03.99, the completion date of the work which Zao Wou-Ki completed in this spring. His art is outstanding and distinctive, lyrical and emotional, consistent with his personality.” In the catalogue preface of the exhibition “1948-1999, A Retrospective of Zao Wou-Ki” in 1999, the owner of Lin & Lin Gallery in Taipei wrote as such about 01.03.99, which is to be offered at the upcoming auction. The work also served as the cover of the retrospective catalogue as the representation of the artist’s achievement over the past 60 years.

Zao Wou-Ki

01.03.99

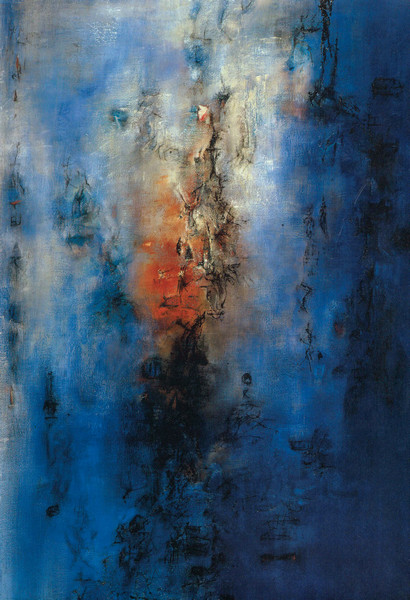

01.03.99 epitomised the many facets of Zao Wou-Ki’s art and the true meaning of painting that he spent his life pursuing. Through colours and lines, his talent was fully unveiled. Differentiated from the decentralised composition and the technique of heavy ink shading in most works from the “Infinity period,” Zao chose bright orange and blue in strong contrast for this work. Using bold brushstrokes, he set the main hue through vast expanses of orange, exuding warmth and fertility, between which the black lines wind through. Such an arrangement has carried on the feature of “partly obscured, trembling and fractured lines” from the “Oracle period” in the 1950s, unfolding the relationships of his painting and the traditional aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy.

On the vertical axis of the painting rises a black ridge, stretching downward along with twisting lines and forming a ridge-shaped structure expanding outside from the centre, which is characteristic of Zao’s compositions in the 60s. But the work has the distinction of a lyrical atmosphere, relaxed and calm because Zao was no longer trying to “prove himself” as he did in the prime of his career. The arrangement of the painting appears spontaneous, reflecting the liberality and open-mindedness of him as an octogenarian. At this point his outlook on life is just like the magical blue sky in the painting, vast and boundless. The perceptions and joys of life embedded in the work are reminiscent of the poetry of Du Fu in the Tang Dynasty, particularly the verse “there is crystal blue sky above, yielding brilliant light that illuminates the ornate terrace” from the poem “A Winter View of Jinhua Mountain.”

Imperial robe in Qing Dynasty

A New Take on Ink Art

In the middle area of the picture, the seemingly suspended peach pink spreads gently from the left side, accompanied by brushstrokes of bright yellow, white, and blue, further enriching the layers of space. There exists no specific imagery, while the traces of the existence of human beings and nature are evident. As the French art critic Claude Roy said, “[Zao’s paintings are ] deprived from trees, rivers, forests, hills, but full of waterspouts, jiggles, spurts, impulses, drips and diaphanous coloured magma dilating, coming out and bursting forth. It was called by new concerns, dramas and invasions.” Its inextricable relationship with the aesthetics of Chinese ink painting and the landscape painting in Song and Yuan dynasties lies beneath the Western oil paints which are bright and full of vigour. As the art critic, Jia Fangzhou, pointed out, “This is an artistic approach that doesn’t belong to any Western artist!”

Zao Wou-Ki

05.05.55

Painted in 1995

195×130 cm

Moreover, a black rubbing of totem appears in the upper right of the orange ground, an uncommon feature in his paintings. Zao was an expert in traditional Chinese rubbings of tablet inscriptions. In 1967, he co-authored the book, Estampages Han, with Claude Roy, interpreting the relationship between stone rubbings and the Han Chinese culture. However, this is the first time that he incorporated rubbing into his painting, from which we can see his constant exploration of new techniques. As he once said, “I want every painting to be bolder and more unrestrained than the previous one.” Even in his late years, Zao continued to pursue perfection and challenge himself.

The artistic practice of Zao Wou-Ki from the early years to the 1990s is a journey from the East to the West, and finally returning to his inner self. Through 60 years of artistic exploration in colour, space, light, he reveals to us the richness and beauty he saw with his eyes and his heart, and leads us to the depths of the world through his paintings.

Zao Wou-Ki

07.04.61

Painted in 1961

195×114 cm

Zao Wou-Ki

01.04.81

Painted in 1981

260×224cm