- Lot

- Information

by Vita Chen

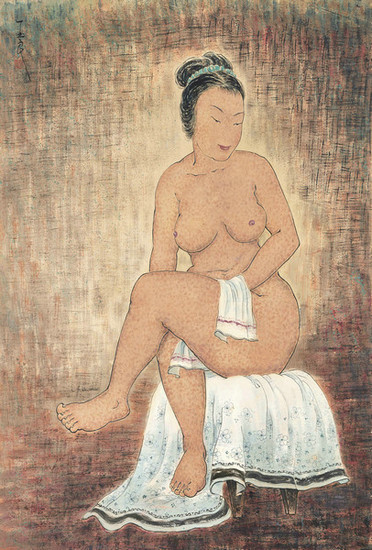

Pan Yuliang

Seated Nude

Approximately painted in 1940-1945

Ink and colour on paper

100 × 70 cm

Pan Yuliang was born in 1895, making her four years older than Zhang Daqian, five older than Lin Fengmian and the same age as Xu Beihong, all important members of the first generation of outstanding Chinese artists which contributed much to the splendour of 20th Century Chinese art.

Never the Weaker Sex

Pan Yuliang’s parents died when she was young and at the age of 14 she was sold by her uncle to a brothel, from where she was bought by customs inspector Pan Zanhua from Wuhu, Anhui. It was his surname she eventually took and eventually Pan also had the opportunity to develop her artistic talent. In 1918, Pan Yuliang was admitted to the Shanghai Art School, where she studied Western painting under Wang Jiyuan and Chinese painting under Zhu Qizhan. The principal Liu Haisu was avant-garde in his artistic style and the first to use nude models as part of the teaching curriculum, a decision that created much backlash from a society that remained very conservative, but it also planted the creative seeds for Pan’s creative work. It was at Shanghai Art School that she first painted a nude model, observing in detail the stylistic language of the human body, and “female nudes” were the most important theme in her later graduation work.

Pan Yuliang sketches human body in her studio

In 1921, Pan Yuliang passed an exam for publicly-funded overseas study and enrolled on a program of advanced study in France, first attending the National School of Fine Arts in Lyon, followed by the National School of Fine Arts in Paris and Accademia di Belle Arti di Roma in Italy. After graduating, in 1928 she was recruited by Liu Haisu to return to her alma mater as a teacher and later rose to become director of the Shanghai Art School Graduate School, dedicating herself to teaching and producing art. Pan’s unique and powerful artistic vocabulary conquered viewers and after returning to China she held five solo exhibitions in Shanghai and Nanjing up to 1937, each one a cause of much controversy. For example, the solo exhibition she held at the Overseas Chinese Guesthouse in Nanjing in May 1935 attracted more than 5,000 visitors over seven days, with renowned art and cultural figures, including Zhang Daofan, Xu Beihong and Li Jinfa publishing commentaries in the Central Daily News, in which they discussed their impressions of the event. Xu was particularly impressed with what he saw, writing: “Pan takes risks to explore the beauty of creation in a way no scholarly painter has for 300 years ... today art is in decline ... scholarly gentlemen have nothing to offer, paling in comparison to Madame Pan Yuliang.” Such a comment underscores her lofty position in the Chinese art world at that time.

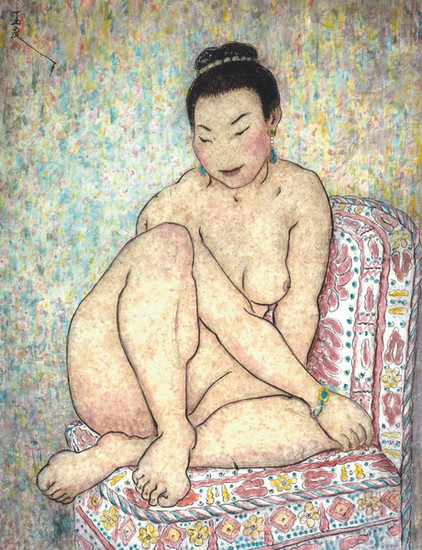

Rare Seated Nude on a Sofa

Painted in 1961

81×63 cm

A World-Renowned National Treasure

From 1937-1977, Pan Yuliang lived in France and won 21 individual art awards, with her works shown in salon exhibitions and national art museums on 47 occasions. From 1942 to 1947, the Paris Municipal government bought several of her ink and sketch works. Moreover, from 1956 her art works were designated important cultural artifacts by the French government and their export banned without an official license, a reflection of the esteem with which the French art world and officialdom held Pan’s artistic achievements.

From a prostitute to director of the Shanghai Art School Graduate School and a position as what British art historian Michael Sullivan called “one of the top Western painters in China,” Pan’s successes were astounding and a testament to her desire as a modern woman to pursue the truth, her perseverance and towering talent. Pan’s works have been collected by the Pompidou Center, Cernuschi Museum, Paris Museum of Modern Art, National Art Museum of China and Anhui Provincial Museum. However, very paintings by Pan Yuliang have ever been sold at auction, which makes it a distinct honour for us to present in our spring auction Seated Nude completed at the peak of her most creative period in the 1940s. It is also the largest ink and colour work to be sold on the secondary market for almost a decade, making this a rare opportunity not to be missed.

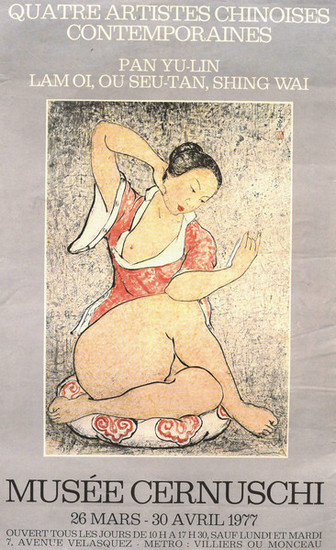

A poster of Pan Yuliang's exhibition in Paris in 1977

Self-Seeking from the Ancients, Unique Path between East and West

Other than oil paintings, in 1932 Pan Yuliang began to learn calligraphy from the Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, and often sought the counsel of Chinese painters Zhang Daqian and Huang Binhong as she experimented at painting with Chinese xuan paper and ink, which was a medium the artist used the rest of her life and the one through which she showcased her most innovative artistic achievements. In 1938, Pan’s colour and ink painting became more skilled as she entered a golden age of creativity. Seated Nude is an example of work from that period. In the piece, we can see how she borrows from the essence of Eastern and Western painting mixed with her own inimical character and avant-garde expression. In this sense, Pan Yuliang can be said to have borrowed from the ancients as she searched for her self without getting lost in that pursuit, enabling her to plot a unique path between East and West.

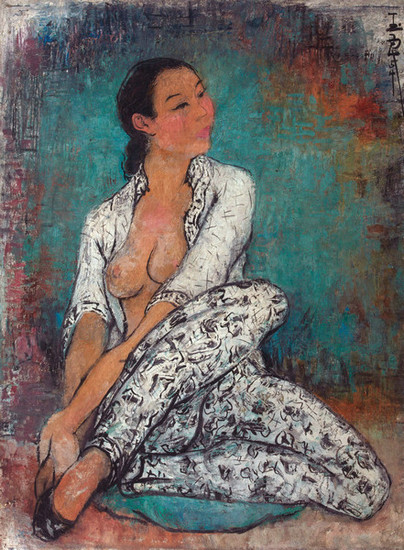

Pan Yuliang

Look into the distance

Painted in 1945

61×45 cm

In this large painting, Pan employs her well-honed Chinese line drawing technique to depict a naked woman sitting gracefully on a printed cotton cloth at the centre of the work. The twisting and turning black lines reveal the confidence of the painter, sometimes steely and powerful, but on other occasions soft and unbroken. From the posture of the woman we can see Pan’s mastery of Western anatomy, the crafting of a three-dimensional feel she learned from sculpture and the internal connection between these and Chinese calligraphy. In the picture, the woman’s left leg is placed over the right, the slight turning of the body adding to the dramatic tension of her curves, while also avoiding the need to depict her exposed genitals, the embodiment of modest beauty in a provocative scene. In her hand, the woman holds a towel to dry herself, revealing a sense of comfort after bathing, with dark eyebrows, almond eyes and a tranquil smile on her face as she quietly enjoys this carefree moment of leisure. At the same time, the woman wears her hair in a bun, the crucial touch being a graceful and elegant green beadwork hair accessory, which in combination with her black hair and eyes identifies her as coming from China. The blue-died floral cloth on the chair adds a sense of simplicity and sincerity to the painting. Moreover, although Pan Yuliang uses the pointillism of the Western post-impressionist school to depict the skin of her subjects, she also adds an innovative flourish with skin colour points of different size and depths. Through the pauses in between layers and dry/wet colours, Pan not only imbues the figure with a sense of volume she simultaneously showcases a rich sensuality and litheness, an innovative approach that was completely new.

In terms of the background in the painting, Pan Yuliang uses the iconic cross texture strokes using the layering, overlapping and smudging of coloured lines to resemble the texture of Western painting. This marked a departure from the leaving of blank space in traditional ink painting and helped to craft a deep spatial view and changes in light that highlight the main figure. Pan was the first painter to ever adopt this method of expression in traditional Chinese ink painting. In this work, she also challenged a long standing traditional ink painting taboo, which explains the relative paucity of nudes in the medium, and thereby breathed new life into the tradition. The former director of the Guimet Museum in Paris Vadime Elisseeff said: “Pan Yuliang uses the brushwork of Chinese calligraphy to depict everything, but she is in no way restricted by that tradition, a contribution that enriches modern art. Pan’s works are combinations of Eastern and Western painting to which she adds herself. She uses straight and curved lines to depict scenes and these vibrant lines come to life on paper, each unique one in its own right, naturally constituting a work that is realistic and concrete.” The Eastern and Western cultural elements in this painting fit together in a way that highlights their perfect fusion and innovative use.

Pan Yuliang

Self Bronze Sculpture

60.5×25×19 cm

The Joy and Splendour of Life

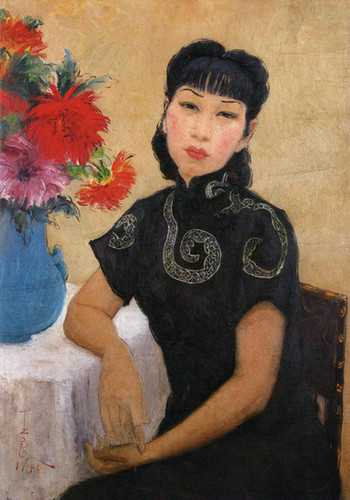

Seated Nude was painted in the early 1940s, shortly after Pan Yuliang resigned as a teacher and during her first few years in Paris. In April 1939, her husband Pan Zanhua sent xuan paper and painting brushes from Chongqing, an indication that he supported her artistic pursuits. In September 1939, following the outbreak of World War II Pan moved to the outskirts of Paris where she dedicated herself to painting, and it was not long until she reached her creative peak. For example, the universally praised oil painting Self Portrait in which Pan is depicted wearing a black embroidered qipao was completed in 1940, and it was against this backdrop that the colour and ink work Seated Nude was painted. At that time, separated from her husband, Pan put her past achievements and position as a professor behind her and focused on life alone overseas. Add to that the fact that she witnessed the cruelty of war first hand and the figures in many of Pan Yuliang’s works at this time have expressions that can best be described as hinting at mournfulness and pride. However, Seated Nude hints at a different emotional state of mind.

“You say that the most important thing in life is the meeting of minds not bodies. ‘Tacit understanding’ is something supernatural that allows two hearts to be together even if in different places as with the meeting of minds.”

──a letter from Pan Zanhua to Pan Yuliang

Pan Yuliang

Self-portrait

Painted in 1940

90×64 cm

Through the sweet smile and the frank and open physical posture of the figure in Seated Nude, Pan Yuliang perhaps gives voice to the idea that despite the melancholy of being far from a loved one, if two minds are one then despite the distance between them there can still be happiness and joy in spirit. However, living in Paris Pan was far from conservative Chinese Society and freed from the gossip and rumours that followed her throughout her life. It also extricated her from her role as a concubine to Pan Zanhua and the inherently embarrassing and lowly position of two women serving one man. Pan Yuliang was now free to dedicate herself to the pursuit of art and living the life she wanted. The proactive character with which the artist imbues the central female figure in Seated Nude is also a reflection of her life at that time. It honestly depicts her praise of life as well as her pursuit of truth. Indeed, it is through these qualities that the work transcends the bounds of a simple female nude, as they elevate it to a higher plane replete with artistic meaning and philosophy, one that surpasses the ancients and amazes contemporaries with its splendour.

A group photo of Pan Yuliang (front row, fourth right) and members of the French Association of Female Artists